It is a good idea to bring another smaller bag so that unwanted clothes can be kept in it at the hotel or camp when you go on trek. We recommend keeping the weight under 15 kg as the domestic air carriers have baggage allowance of 10 kg maximum and + 5kg cabin baggage (totally 15 kg). Excess luggage charge is 1.5 -2 $ per every 1 kg. Before leaving for a country trip, you can leave extra weight luggage in luggage storage room of the hotel...

View More »Register and receive interesting information and travel news

Our trip was very nice. We didn't expect so much fun, peace and lots of information. Our guide Bolroo was much knowledgeable and very kind. Driver ... was like professional, always carefelly driving out holes on the road.

~ Claudio, Italy

Mongolia in 15-19 centuries

Part I. Buddhism art

Tibetan Buddhism, a highly ritualistic religion with a huge pantheon of gods and goddesses, inspired the religious art of Mongolia. As in most religions, there is a need to create cult images in painting and sculpture, as well as ritual objects and other paraphernalia associated with worship of the deities.

The objects are the result of the second wave of conversion to Buddhism in Mongolia. They are inspired by Tibetan art. There was a great deal of cultural exchange and travel between Tibet and Mongolia; Tibetan lamas proselytized in Mongolia, and Mongolians went on pilgrimages to Tibet. When young Mongolian monks traveled to Tibet returned to Mongolia, they brought religious objects home with them. As a result, there was much mingling of artistic styles between Mongolia and Tibet.

Sculptures

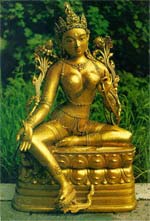

In the 17-18 century the famous and the greatest sculptor in Buddhist countries was the Bogd Zanabazar (1635-1723). He was educated in Tibet and later proclaimed by the first Mongolian Dalai Lama. Upon his return to Mongolia in 1651, he was accompanied by hundreds of Tibetan lamas and many artists and craftsmen, sent by the Fifth Dalai Lama to propagate the faith and to build monasteries. Zanabazar's greatest contribution to Mongolian art is his gilt bronze sculptures and 21 Taras.

In the 17-18 century the famous and the greatest sculptor in Buddhist countries was the Bogd Zanabazar (1635-1723). He was educated in Tibet and later proclaimed by the first Mongolian Dalai Lama. Upon his return to Mongolia in 1651, he was accompanied by hundreds of Tibetan lamas and many artists and craftsmen, sent by the Fifth Dalai Lama to propagate the faith and to build monasteries. Zanabazar's greatest contribution to Mongolian art is his gilt bronze sculptures and 21 Taras.

The sculptures of Zanabazar portray youthful figures and are beautifully proportioned. Their facial features are characterized by high foreheads, thin, arching eyebrows, high- bridged noses, and small, fleshy lips.

The jewelry is exquisite, especially the long simple strands of beads that hang across the figures' torsos. His works have a peaceful and contemplative look and share many characteristics with Nepalese sculptures.

The sculptures of the Zanabazar school are generally made in two pieces; the body and the pedestal are made separately and then soldered together. Most of the sculptures are gilded, and the mercury gilding is especially beautiful. The lotus pedestals of the sculptures by Zanabazar and his school are distinctive. Instead of the oval and rectangular throne types common in Tibet , they show a preference for circular or drum-shaped pedestals and semi-oval pedestals with tall bases such as the one for the four Taras.

The Zanabazar school of sculpture is distinguished by the beautiful and varied lotus petals, which are not to be found on the sculptures of Tibet , Nepal , and China . There is much variation; the petals can be plain, single, double, wavy, scalloped, or with the tip bent forward.

Images in Mongolia , following the Tibetan tradition, were consecrated after they were made. Sacred objects such as rolls of prayers and other relics were inserted inside the statue, and the base was sealed with a metal plate. The standard decoration for the base plate is an incised double dorje. On the sculptures made by Zanabazar or his school the base plates are inserted in a different way. In general, they were carefully made to fit snugly over the cavities, not held in position by chisel points on the base, Sculptures made by Zanabazar and his school are rare even in Mongolia and are considered national treasures.

Painting

The Buddhist paintings of Mongolia are directly related to the painting tradition of central Tibet . They are executed on cotton stretched on a frame. The cloth is first sized with a solution of chalk, glue, and milk vodka, then polished with a smooth stone when dry. The image is then drawn in charcoal according to the proportions or sometimes the artist may use a pounce. The pigments consist of mineral and vegetable colors, mixed with yak-skin glue. The finished piece is framed with silk brocades, and a thin stick and a wooden roller are inserted at top and bottom for hanging.

In 16-19 centuries some Mongol artists used one hair of horsetail as their brush and earthen paints to make their painting more decorative and unique ones and they spent hundreds of days for their painting. The paintings drawn by these items are still used in Buddhist temples in the central part of Mongolia.

Mongolian paintings, following Tibetan traditions, can be painted on white, red, or black backgrounds. While the majority of paintings are executed on a white background, there are special images painted on a red ground . Paintings on a black ground often depict wrathful deities, and are kept in the special room in the temple reserved for guardian deities.

Like Tibetan thangkas, Mongolian paintings are noted for their fluid line work, contrasting colors , and the intricate designs in gold. Characteristic Mongolian elements can be detected, such as the lotus pedestal in the thankas.

Appliqués

The appliqué of Mongolia is like a giant thangka or painting. The embroidery needle and thread take the place of brush and ink, while pieces of silk and brocade are transformed into areas of color. Where one finds gold highlights in Buddhist paintings, in appliqués one finds gold threads, carefully couched along the edges, and golden brocades are cut into jewelry shapes.

Appliqué thangkas came into Mongolia together with Vajrayana Buddhism. Mongolians are familiar with this technique for the excavated felt carpet of the Huns from the Noyon Uul burials already showed a combination of embroidery and appliqué. The Urga area is especially renowned for its appliqués used for decorating temples and palaces, done by women under the supervision of famous artists in the late 19 and early 20 century.

Appliqués are called "silk paintings" in Mongolia because silk is the main material for creating this art form. Silk has been imported from China since ancient times. Any scraps left over were fashioned into elaborate temple hangings tassels for drums and other ritual objects, and, of course, made into appliqués.

The appliqué of Dorje Dordan is one of the best in Mongolia . It is pieced t ogether with many interesting types of silk and brocade, including scraps of dragon-robe material. The appliqué of Begze is further ornamented with tiny coral beads. This addition of gems such as coral, pearls, and turquoise in appliqué is a purely Mongolian practice, and not found elsewhere.

Book Decoration

Mongolians realized early that books were essential in disseminating Buddhism. Although Tibetan was the liturgical language of Mongolia , Kanjur and Tanjur were translated into Mongolian and published. Sutra-printing took place in many monasteries of Mongolia.

The same technique used in painting is applied to book decoration. Mongolian sacred texts are outstanding for their lavish ornamentations, such as the Sanduijud, with the text embossed on sheets of silver and gilded. In another example, the "nine gems," gold, silver, coral, pearls, lapis lazuli, turquoise, steel, copper, and mother-of-pearl, were ground up for use as pigments and the sutra was written in the nine colors on black paper in a fine calligraphy.

Mongol scribes illustrated the title page on paper and then framed it with softwood, which was then embellished with Chinese brocades. The back covers of Mongolian sacred texts, following Chinese tradition, often depict the Guardians of the Four Quarters.

Part II. Applied Art

Mongolians are an artistic race and have a tendency to decorate every item on their body, inside their Ger , and on the trappings of their animals. This is demonstrated not only by their highly developed handicrafts but also by many folk sayings in which knowledge is demanded from men and manual dexterity in women. Metal work reached a high level of craftsmanship back in the time of Khunnu state. It is known that iron and steel were worshipped by Mongols in the 13-th century.

Mongolians are an artistic race and have a tendency to decorate every item on their body, inside their Ger , and on the trappings of their animals. This is demonstrated not only by their highly developed handicrafts but also by many folk sayings in which knowledge is demanded from men and manual dexterity in women. Metal work reached a high level of craftsmanship back in the time of Khunnu state. It is known that iron and steel were worshipped by Mongols in the 13-th century.

It was customary to see the new year at the forge bellows making the ritual iron strips. In olden days foreign travelers were amazed to see that all Mongolian cattle-breeders, poor thought they were, had richly ornamented clothes and jewelry at home. Every item of a cattle breeder's household, however, insignificant had apart from its utilization value, merits of an object of decorative applied to art.

Female ornaments –rings, bracelet, locks, headgear, ear*-rings pendants and hairclips –were indeed outstanding works of craftsmanship. Household objects, including knives, flints, vessels, pieces of furniture, stirrups, and horse gear were very decorative. The garments and footwear were splendidly decorated, especially the Mongolian high boots with upturned tips. Among the traditional folk crafts were metalwork, bone carving, leather work, embroidery and appliqués.

What distinguishes Mongolian applied art is the fact that it is very laconic without anything superfluous or showy. Works of applied art are structurally purpose oriented and well done. With very few exceptions, Mongol used handcrafted wares and jewelry produced at home rather than brought from other countries. That was dictated by the condition of nomad's lifestyle.

Mongols were preferred to use their national cups made from hollowed tree roots, which were set in silver decorated with engraved or chased ornament. Each Mongol always had such a cup with him. The main technique employed by Mongolian jewelers –silver filigree, gilded and inlaid with semi precious stones – found consummation in female headgear, pendants and hairclips.

Mongolian filigree is noted for its excellent workmanship and durability, the latter being the main requirement in conditions of nomadic life. Mongolian craftsmen employed various techniques in making saddles and horse gear , including slitting, cutting and engraving in steel, chasing in silver etc. the most sophisticated jeweler's techniques were widely used in decorating flints and knives.

Nice examples of applied art works are some of the fancier containers, belonging to the wife of Bogd Khan are made of precious metals and embellished with semi-precious stones. The tinder pouch or flint and steel set consists of a small leather pouch with a strip of steel attached to its lower edge. Depending on one's station in life, the tinder pouch can be a utilitarian piece, or it can be a work of art.

Ornaments and Volutes

The two major types of pattern in Mongolian decorative art are the ornament, "which creates the rhythm" and volutes-scrolls, which emphasizes the form. Together, they create balance. There are five types of Mongolian motifs: geometric, zoomorphic, botanical, shapes from natural phenomena, and symbols.

The two major types of pattern in Mongolian decorative art are the ornament, "which creates the rhythm" and volutes-scrolls, which emphasizes the form. Together, they create balance. There are five types of Mongolian motifs: geometric, zoomorphic, botanical, shapes from natural phenomena, and symbols.

Geometric designs include alhan hee, or meander; tumennasan, or eternity pattern; olzii utas, or "happiness" knot; khan buguivch, or khan's bracelet; hatan suih, or princess's earrings; zooson hee, or coin; and tuuzan hee, or ribbon.

Zoomorphic designs consist of hornlike and nose-like scrolls; the four friendly animals (elephant, monkey, hare, and dove; cat, the four strong animals (lion, tiger, dragon, and the mythical bird Garuda); the twelve Asian zodiac animals (rat, ox, tiger, hare, dragon, snake, horse, ram, monkey, rooster, dog, and boar); and the circle made up of two fish (yin & yang).

Botanical motifs are represented by the lotus (purity), peony (prosperity), and peaches (longevity). Water, flames, and clouds are shapes from natural phenomena. Symbols are The Eight Auspicious Symbols, the Seven Jewels of the Monarch, and the Three Jewels. Many of these designs are of Tibetan and Chinese origin, but they merged with the basic Mongolian motifs into a rich decorative repertoire.

Among the Mongolian craftsmen, the craftsmen, who was born in eastern part of Mongolia and educated eastern schools on decoration art, are considered as the best ones and their metal work is very unique. Because they used zoomorphic designs specialized on zodiac animals and natural phenomena designs. Generally, Many of these decorative motifs can be found on the embroidered cases for snuff bottles, another object which is attached to the Mongolian's belt. The bag is worn doubled over one's belt, thus keeping the bottle secured.

Mongolian painting

The synthesis of the canons for religious paintings during the Buddhist renaissance period and the realistic manner of early Mongolian secular art gave rise to an original genre of painting that has come to be known as Mongol Painting. It is noted for a variety of forms and techniques and its artistic manner is wide-ranging and easy-going.

Mongol painting is associated with a special mode of thinking and a way of seeing the surrounding world. The most outstanding representative of Mongolian painting is B.Sharav nicknamed the Joker. He was sent to a monastery at an early age , but left it in adolescence to become a wandering lama. Many years later he depicted the impressions of his travels in his famous picture One of Mongolia's days in which he used earthen paints. The composition of the picture is very intricate embracing as it does practically the entire spectrum of the Mongols' everyday life. All the scenes depicted are full of fascinating dynamism and have touch of gentle irony.

Narrated by tour guides of Blue Mongolia Tour

Call our travel expert at:

Tel worldwide: 976-9985 0823, 976-88807160

Tel domestic: 976-70110823

Fax: 976- 7011 0823

Skype: Blue Mongolia Travel agency

Ulaanbaatar Time Now (GMT+7):

Our Office hours is 9:00 to 17:00 Monday to Friday.

Write and send your request at:

info@bluemongolia.com, service@bluemongolia.com

Post address:

Reciepent 99850823, Building 80, Ikh Toiruu Street, Sukhbaatar District, Ulaanbaatar 14192, Mongolia